When rights clash in the workplace, a balance must be struck.

In a society with diverse religious beliefs, employers are challenged not only to be tolerant, but also to accommodate diversity in the workplace.

Given employers’ need for efficiency in producing goods or providing services, the question is to what extent employees’ religious beliefs and practices must be accommodated. What guiding principles have the courts provided?

For instance, an employer asks an employee to work on a Sunday as required by the employee’s employment contract, but is informed that the employee is a committed Christian whose beliefs require him to attend church and to observe the day as a day of rest.

Hence, he refuses to work as required. May the employer take disciplinary action against this employee for insubordination (refusal to obey a lawful instruction)?

Or, assume that a Muslim employee asks for time off on a Friday afternoon to attend prayers at the local mosque. This happens to be the busiest time in the employer’s shop, and letting the employee go would result in a loss of revenue. Accordingly, the employer refuses, but the employee still leaves his workstation to attend prayers. Can the employee be disciplined for insubordination or being AWOL?

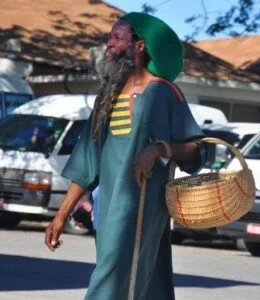

Another example: A Rastafarian arrives for a job interview at a bank. He is an excellent candidate, but makes it clear, when asked whether he would be prepared to cut his dreadlocks to comply with the bank’s policy on employees’ dress and appearance, that he will not, because it would offend his religious and cultural beliefs.

As a result, the bank does not appoint him. Does this man have an unfair discrimination claim against the bank? These and other interesting questions relating to religion have recently come before the courts. The cases involved, among others, Rastafarians who worked for the Department of Correctional Services being dismissed for refusing to adhere to the department’s policies, which prohibited the wearing of dreadlocks.

Another example was a case involving security guards who refused to trim their wild and long beards, regardless of the strict rules regarding maintaining a clean and easily recognisable appearance in the security industry.

Other cases have involved a Jew and a Seventh Day Adventist refusing to work on a Saturday.

The starting point in all the cases is that employees, like any other citizens, have the right to freedom of religion. This is guaranteed by the Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

It is also provided for in Chapter II of the Employment Equity Act, which prohibits unfair discrimination in any employment policy or practice, as well as section 187 of the Labour Relations Act, which prohibits the dismissal of employees on the basis of their religious beliefs.

However, they have also indicated that the right to practice one’s religion, like all other fundamental rights, is not absolute. The right to freedom of religion may be limited by other rights – in this case, the employer’s right to freedom of economic activity (i.e. the right to conduct business).

However, in the same way that an employee’s rights are limited by employers, the reverse is also true: the employer cannot ride roughshod over the rights of employees. When rights clash, a balance must be struck.

The courts have developed two principles in striving to achieve this balance. The first is the obligation on the employee who feels that his or her religious beliefs are being jeopardised or threatened by the employer’s requirements, policies or demands, to make his or her beliefs known to the employer.

If the employer is unaware of the employee’s religious beliefs, it cannot be accused of insensitivity towards such beliefs.

Second, the employer’s requirements must offend an essential element or tenet of the employee’s faith. Put differently: compliance with the tenet must be compulsory, not voluntary.

If, for example, Sunday observance is encouraged by the employee’s faith without it being compulsory, the employee may not insist on being treated differently to other employees who are required to work on a Sunday.

If these facts have been established, and the employee complains to the Labour Court about unfair discrimination or “an automatically unfair dismissal,” as the case may be, the employer will be required to prove two facts.

First, that the rule is an “inherent” requirement of the job. This means that given the employee’s religious beliefs, the job cannot be done at all by that employee. Or that the job cannot be done according to the requirements that are generally accepted as reasonable in the particular profession or business sector.

Second, that the employer has taken reasonable steps to accommodate the employee’s religious convictions.

For instance, this might include attempts to accommodate the employee whose belief prohibits Sunday work on a shift that does not include Sundays. Or requiring a Rastafarian to neatly tie back his hair while on duty.

If an employer was unaware of an employee’s convictions at the time of, for instance, instructing him to work on a Sunday, the employee will not be successful in challenging the employer’s decision to discipline or even dismiss him for refusing to adhere to instructions. Even if the employee raises his or her religious beliefs with the employer, it is not enough for the employee merely to say: “Your instruction will be disobeyed because of my beliefs.”

The employer may insist on the employee providing some credible proof (e.g. an affidavit from a church minister or rabbi) as to the centrality of the particular belief to the employee’s religion.

This will not be necessary where it is well known that certain religions require strict adherence to certain practices – for instance, male Muslims attending Friday prayers, or (true) Rastafarians not being permitted to cut their dreadlocks.

The balancing of religious rights in the workplace will remain a sensitive and emotive matter, but at least employers have some guiding principles when making decisions on how to accommodate these rights.

- For more labour advice by Barney Jordaan, go to www.labourwise.co.za